A bitterly cold evening in March of 2021, Syracuse police discovered 93-year-old Connie Tuori brutally murdered in her apartment at the Skyline building. Officers stepped around used syringes, scattered drug paraphernalia, and human waste on the hallway floors as they investigate the scene. The corridors, dimly lit and thick with the smell of human waste, rotting garbage, and filth, told a grim story: neglected spaces breed desperate behavior. Neighbors would later describe screaming in the night, strangers roaming the halls at all hours—yet intervention and accountability never arrived in time to save an elderly woman living out her final days in fear. This nightmare at the Skyline is not an isolated tragedy. Across Syracuse, properties like The Skyline have faced their own grim headlines—homicides, rampant drug use, and unchecked violence. And if “Good Cause Eviction” goes into effect, many property owners fear that dangerous environments like these will become even harder to reclaim and revitalize.

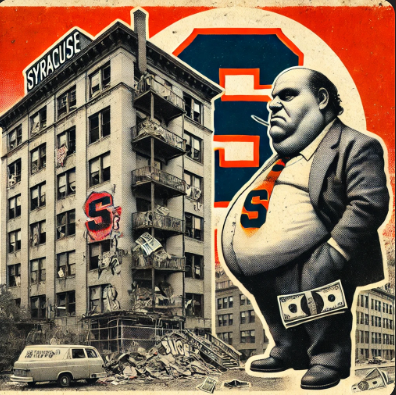

Now we introduce the “Greedy Slumlord”, a creature you’d think was a common sight in the streets of Syracuse, feasting on inflated rents and turning a blind eye to leaking roofs and flickering lights. Legend portrays the Slumlord; rapacious, uncaring, driven by greed and profit seeking at the expense of human dignity.

The Greedy Slumlord Myth

Yet, in reality, profit demands a different approach. To simply secure the money needed for a purchase, our so-called “slumlords” must satisfy sophisticated and complex requirements set forth by the lending institutions who want to make sure their loans are properly collateralized against good assets. I am an investor myself, I am not here to defend the investor or the landlord; if being a Slumlord generated more money than being a good landlord, then surely there would be more slumlords. Unfortunately for my Slumlord Brethren, to make money; the buildings must be well taken care of.

The lenders require an in-house inspector, and engineering report, an appraisal, a City Code Inspection, a City Fire Marshall Inspection, and Electrical Inspection, and the list goes on.

They note the building’s occupancy rates, test the fire alarms, and scrutinize electrical panels. If the property fails even one key checkpoint, financing evaporates—along with the dream of any lucrative return.

Thus, the investor has no choice but to pursue a clean, secure, and legally compliant environment. It’s not compassion alone prompting this behavior; it’s a bank mandate. A decrepit building filled with unchecked crime won’t pass muster. Surprisingly, the “greedy slumlord” is forced to become the meticulous steward—mending roofs, renewing safety certificates, and ensuring tenants aren’t living in perpetual squalor. Sometimes, profit and good housing can be closer allies than we think.

And so, we arrive at a remarkable scene: entire blocks of vacant buildings, their windows shattered and walls peeling, stretching out across a once-vibrant urban landscape. These properties are little more than wastelands—broken shells haunted by memories of better days.

Yet to a new breed of investor, these forlorn buildings stand as glimmering opportunities for renewal and, ultimately, profit. By acquiring multiple problem properties at once, developers can align renovation timelines, coordinate security enhancements, and introduce upgrades on a broad scale.

Good Cause Eviction Hampers Turnarounds

Under Good Cause Eviction, landlords can face a near-permanent obligation to keep tenants whose rent is paid—even if those tenants are linked to criminal activity, chronic disturbances, or unsafe living conditions. The courts may decide that the timely payment of rent outweighs lease violations like property damage or creating a hostile environment, landlords are robbed of their primary tool for restoring order and safety. In turn, properties teeming with problematic behavior remain uninviting to serious investors seeking to renovate and improve neighborhoods.

A further complication is how this rule effectively pushes landlords to adopt annual rent increases to the maximum allowable amount. If they don’t raise the rent each year, they risk losing the right to do so in the future as the law can treat a sudden, larger hike as “unjustified.” This approach penalizes even well-behaved tenants.

Locked in Decay

One of the biggest deterrents for would-be investors is the near-impossibility of acquiring a blighted, crime-ridden building if it’s already occupied by tenants effectively “locked in” under Good Cause Eviction. Even if the buyer plans extensive renovations, those improvements often require vacant units. Yet if the law sees timely rent payment as reason enough to stay, landlords are stuck with the same problematic residents. Meanwhile, the very conditions that make the building undesirable in the first place—rampant drug use, vandalism, or regular police calls—remain baked into the property. New ownership can’t justify the cost of major upgrades when it’s impossible to free up units for real repairs or bring in tenants who value a cleaner, safer environment.

Looking for Property Management in Central New York?

RenPro manages residential properties across the Syracuse metro area and beyond.